There is a new phenomenon, more prevalent in the English-speaking world but not unheard of in other places, the so-called “cancellation”. To distinguish it from regular criticism, let us say it also must involve a firing, a removal from a position of leadership, or the loss of endorsements or influence. In other words, there is the loss of income, or at least of previously earned influence.

It is still hard to distinguish a well justified loss of influence from a cancellation. If someone turns out to be a jerk or an incompetent, then they obviously need to step down. True cancellations involve a concerted effort from a group which has political goals and hopes to further their influence. This can be consciously planned or reflexive and grass-roots. Either way, it is a political push for influence. Even still, I don’t see a thick bright line between a cancellation and a regular fall from grace. Was Louis XVI deservedly punished, or was he cancelled really hard? I cannot tell. Continue reading

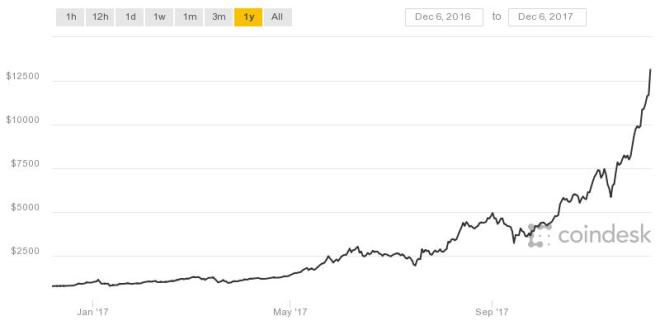

Nevertheless, as a self-respecting economist, I want to make a prediction and test my accuracy. I predict that in exactly two years, on Dec. 6th, 2019, Bitcoin will be valued at less than $3000.

Nevertheless, as a self-respecting economist, I want to make a prediction and test my accuracy. I predict that in exactly two years, on Dec. 6th, 2019, Bitcoin will be valued at less than $3000.

With the DJIA at 25800 today, it does seem appropriate to think about the next recession. Whenever that hits, and whatever shape it will take, I venture that the next recession can be classified into two broad categories:

1. An inherently unstable mismatch between value and incentives, usually in decisions of consumption or investment in one particular area of the economy. The classic example is the last housing bubble. In such situations, overconsumption or overinvestment in one particular area of the economy ends abruptly and this leads to a pervasive feeling of uncertainty, which spreads out into non-affected sectors and further damages the economy.

2. Prolonged good times in the economy lead to loss of discipline. Business and practices which are not viable when subject to even the smallest economic shocks, or even a small drop in consumer confidence, accumulate. This decay is not necessarily restricted to a specific area of the economy. Usually, some meaningless event leads to a sense of economic uncertainty, which is magnified by the runaway failure of the said marginal businessses.

Any honest economist will admit that it is really hard to say anything specific. One needs to know many sides of the economy in detail to venture a reasonable guess. My best guess right now is that the recession will be in category 2 above. The confidence I have in this prediction is low.

Arguments against some causes for a future recession I heard mentioned:

A crash of Bitcoin will lead to a future recession: The crash of Bitcoin is expected by everyone. It can reduce disposable income for a large chunk of idiots invested in it, but the market cap of Bitcoin is not very high and it is spread around the world. Most of it is fake value created recently anyway. The actual money circulating through Bitcoin is a couple of orders of magnitude smaller than the market cap. One caveat: most mining happens in China, and China is already dealing with a lot of bad investment. Hopefully, this won’t tip them over.

Mass defaults on unsustainable student loans in the US will cause a future recession: Student loans are backed by the US government. Only a change in policy by the US government will lead to sudden changes in the behavior of loan takers and loan companies. This will happen, but likely not during a recession, and likely not anytime soon. Usually, people are more likely to go to school when the job market is weak, so a recession will only increase demand for such loans.

Unsustainable spending increases on healthcare in the US will reach a tipping point, causing a future recession: The masive spending on healthcare in the US is, indeed, caused by a malfunctioning market with poor incentives for cost control. (Too many unnecessary procedures, Medicare and Medicaid costs determined based on regional averages — so can still inflate if only at a regionally even pace, etc.) Again, as with student loans, the problem is the policy. The behaviour will not change if the policy won’t. One possible issue is that healthcare policies will change as a result of a recession, but it is more likely that the spending will increase during a recession as a measure of protection for the economy.